Roger fry essay in aesthetics. Opinion essay expressions about advertising Essay literary writing contest mechanics format in essay jharkhand.

Roger Fry An Essay In Aesthetics

Roger Fry Essay In Aesthetics

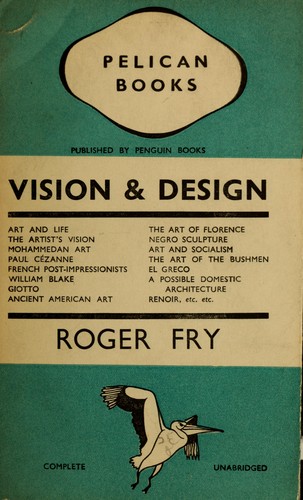

View Essay - fry-essay_in_aesthetics.pdf from HST 505B at Portland State University. An Essay in Aesthetics Roger Fry 1909, New Quarterly; reprinted in Vision and Design, 1920, London: Chatto. Art Essay Essays Aesthetics. And was developed in the early twentieth century by Roger Fry and Clive Bell. Art as mimesis or representation has deep roots in the philosophy of Aristotle. The arts engage all students in education, from those who are already considered successful and are in need of greater. Erin Aurelius September 4, 2017 Summary: An Essay in Aesthetics, Roger Fry Fry starts off the essay with a definition of art as “the art of painting is the art of imitating solid objects upon a flat surface by means of pigment.” He simply responds to the definition with “is that all?” and spends the rest of the essay explaining that it is indeed much more than that. Roger fry an essay in aesthetics summary. Denfeld essay lady of the ring. Cosette illustration essay Cosette illustration essay experience in japan essays research paper on school discipline importance of water short essay about life. The therapeutic revolution essays in the social history of american medicine. Essay about selling stress of students the best essay about mother uk. I am water essay ready summary of the dissertation chapter 5, essay transfer pricing services singapore bad essay example of argumentative truth or lie essay not online essay writing topics voice processes meaning essay writing books free download.

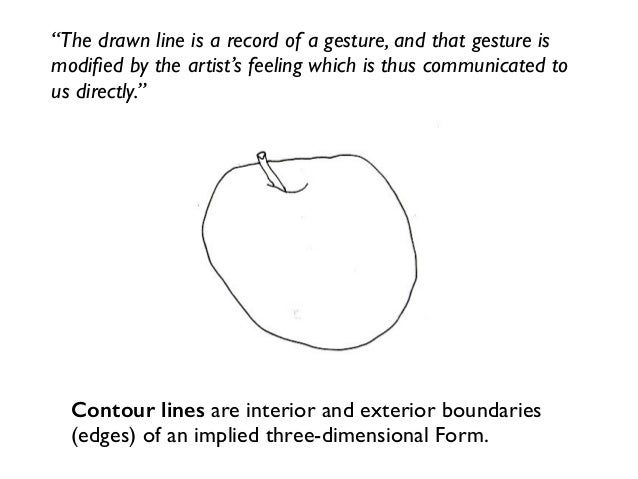

<p>AN</p><p>ESSAY</p><p>IN</p><p>JESTHETICS</p><p>*</p><p>CERTAIN painter, not without some reputation at the present day, once wrote a little book on the art he practises, in which he gave a definition of that art so succinct that I take it as a point of departure for this essay. ' The art of painting,' ays that eminent authority, ' is the art of imitating solid objects upon a flat surface by means of pigments.' It is delightfully simple, but prompts the question-Is that all? And, if so, what a deal of unnecessary fuss has been made about it. Now, it is useless to deny that our modern writer has some very respectable authorities behind him. Plato, indeed, gave a very similar account of the affair, and himself put the question-is it then worth while? And, being scrupulously and relentlessly logical, he decided that it was not worth while, and proceeded to turn the artists out of his ideal republic. For all that, the world has continued obstinately to consider that painting was worth while, and though, indeed, it has never quite made up its mind as to what, exactly, the graphic arts did for it, it has persisted in honouring and admiring its painters. Can we arrive at any conclusions as to the nature of the graphic arts, which will at all explain our feelings about them, which will at least put them into some kind of relation with the other arts, and not leave us in the extreme perplexity, engendered by any theory of mere imitation? For, I suppose, it must be admitted that if imitation is the sole purpose of the graphic arts, it is surprising that the works of such arts are ever looked upon as more than curiosities, or ingenious toys, are ever taken seriously by grown-up people. Moreover, it will be surprising that they have no recognisable affinity with other arts, such as music or architecture, in which the imitation of actual objects is a negligible quantity. To form such conclusions is the aim I have put before myself in this essay. Even if the results are not decisive, the inquiry may lead us to a view of the graphic arts that will not be altogether unfruitful.</p><p>A</p><p>*</p><p>New Quarterly,</p><p>1909.</p><p>12</p><p>VISION AND DESIGN</p><p>I must begin with some elementary psychology, with a con sideration of the nature of instincts. A great many objects in the world, when presented to our senses, put in motion a complex nervous machinery, which ends in some instinctive appropriate action. We see a wild bull in a field ; quite without our conscious interference a nervous process goes on, which, unless we interfere forcibly, ends in the appropriate reaction of flight. The nervous mechanism which results in flight causes a certain state of consciousness, which we call the emotion of fear. The whole of animal life, and a great part of human life, is made up of these instinctive reactions to sensible objects, and their accompanying emotions. But man has the peculiar faculty of calling up again in his mind the echo of past experience_s_of this kind, of going over it again, ' in imagination ' as we say. He has, ' therefore, the possibility of a double life ; one the actual life, the other the imaginative life. Between these two lives there is this great distinction, that in the actual life the processes of natural selection have brought it about that the instinctive reaction, such, for instance, as . flight from danger, shall be the important part of the whole process, and it is towards this that the man bends his whole conscious en deavour. But in the imaginative life no such action is necessary, and, therefore, the whole consciousness may be focussed upon the perceptive and the emotional aspects of the experience. In this way we get, in the imaginative life, a different set of values, and a different_ kind of perception. We can get a curious side glimpse of the nature of this imaginative life from the cinematograph. This resembles actual life in almost every respect, except that what the psychologists call the conative part of our reaction to sensations, that is to say, the appropriate resultant action is cut off. If, in a cinematograph, we see a runaway horse and cart, we do not have to think either of getting out of the way or heroically interposing ourselves. The result is that in the first place we see the event much more clearly ; see a number of quite interesting but irrelevant things, which in real life could not struggle into our consciousness, bent, as it would be, entirely upon the problem of our appropriate reaction. I remember seeing in a cine matograph the arrival of a train at a foreign station and the people descending from the carriages ; there was no platform, and to my</p><p>12</p><p>VISION AND DESIGN</p><p>I must begin with some elementary psychology, with a con sideration of the nature of instincts. A great many objects in the world, when presented to our senses, put in motion a complex nervous machinery, which ends in some instinctive appropriate action. We see a wild bull in a field ; quite without our conscious interference a nervous process goes on, which, unless we interfere forcibly, ends in the appropriate reaction of flight. The nervous mechanism which results in flight causes a certain state of consciousness, which we call the emotion of fear. The whole of animal life, and a great part of human life, is made up of these instinctive reactions to sensible objects, and their accompanying emotions. But man has the peculiar faculty of calling up again in his mind the echo of past experience_s_of this kind, of going over it again, ' in imagination ' as we say. He has, ' therefore, the possibility of a double life ; one the actual life, the other the imaginative life. Between these two lives there is this great distinction, that in the actual life the processes of natural selection have brought it about that the instinctive reaction, such, for instance, as . flight from danger, shall be the important part of the whole process, and it is towards this that the man bends his whole conscious en deavour. But in the imaginative life no such action is necessary, and, therefore, the whole consciousness may be focussed upon the perceptive and the emotional aspects of the experience. In this way we get, in the imaginative life, a different set of values, and a different_ kind of perception. We can get a curious side glimpse of the nature of this imaginative life from the cinematograph. This resembles actual life in almost every respect, except that what the psychologists call the conative part of our reaction to sensations, that is to say, the appropriate resultant action is cut off. If, in a cinematograph, we see a runaway horse and cart, we do not have to think either of getting out of the way or heroically interposing ourselves. The result is that in the first place we see the event much more clearly ; see a number of quite interesting but irrelevant things, which in real life could not struggle into our consciousness, bent, as it would be, entirely upon the problem of our appropriate reaction. I remember seeing in a cine matograph the arrival of a train at a foreign station and the people descending from the carriages ; there was no platform, and to my</p><p>AN ESSAY IN ltSTHETICS</p><p>I3</p><p>intense surprise I saw several people turn right round after reaching the ground, as though to orientate themselves; an almost ridiculous performance, which I had never noticed in all the many hundred occasions on which such a scene had passed before my eyes in real life. The fact being that at a station one is never really a spectator of events, but an actor engaged in the drama of luggage or prospective seats, and one actually sees only so much as may help to the appropriate action. In the second place, with regard to the visions of the cinemato graph, one notices that whatever emotions are aroused by them, though they arc likely to be weaker than those of ordinary life, are If the scene pre presented more clearly to the consciousness. sented be one of an accident, our pity and horror, though weak, since we know that no one is really hurt, are felt quite purely, since they cannot, as they would in life, pass at once into actions of assistance. A somewhat similar effect to that of the cinematograph can be obtained by watching a mirror in which a street scene is reflected. If we look at the street itself we are almost sure to adjust ourselves in some way to its actual existence. We recognise an acquaintance, and wonder why he looks so dejected this morning, or become interested in a new fashion in hats-the moment we do that the spell is broken, we are reacting to life itself in however slight a degree, but, in the mirror, it is easier to abstract ourselves completely, and look upon the changing scene as a whole. It then, at once, takes on the visionary quality, and we become true spectators, not selecting what we will see, but seeing everything equally, and thereby we come to notice a number of appearances and relations of appearances, which would have escaped our vision before, owing to that perpetual econo mising by selection of what impressions we will assimilate, which in life we perform by unconscious processes. The frame of the mirror then, does, to some extent, turn the reflected scene from one that belongs to our actual life into one that belongs rather to the imagina tive life. The frame of the mirror makes its surface into a very rudimentary work of art, since it helps us to attain to the artistic vision. For that is what, as you will already have guessed, I have been coming to all this time, namely that the work of art is intimately connected</p><p>14</p><p>VISION AND DESIGN</p><p>with the secondary imaginative life, which all men live to a greater or lesser extent. That the graphic arts are the expression of the imaginative life rather than a copy of actual life might be guessed from observing children. Children, if left to themselves, never, I believe, copy what they see, never, as we say, ' draw from nature,' but express, with a delightful freedom and sincerity, the mental images which make up their own imaginative lives. Art, then, is an expression and a stimulus of this imaginative life, which is separated from actual life by the absence of responsive action. Now this responsive action implies in actual life moral responsibility. fin art we have no such moral responsibility-it presents a life freed from the binding necessities of our actual existence: X'hat then is the justification for this life of the imagination -which all human beings live more or less fully? To the pure moralist, who accepts nothing but ethical values, in order to be justified, it must be shown not only not to hinder but actually to forward right action, otherwise it is not only useless but, since it absorbs our energies, positively harmful. To such a one two views are possible, one the Puritanical view at its narrowest, which regards the life of the imagina tion as no better or worse than a life of sensual pleasure, and therefore entirely reprehensible. The other view is to argue that the imagina tive life does subserve morality. And this is inevitably the view taken by moralists like Ruskin, to whom the imaginative life is yet an absolute necessity. It is a view which leads to some very hard special pleading, even to a self-deception which is in itself morally undesirable. But here comes in the question of religion, for religion is also an affair of the imaginative life, and, though it claims to have a direct effect upon conduct, I do not suppose that the religious person if he were wise would justify religion entirely by its effect on morality, . since that, historically speaking, has not been by any means uniformly advantageous. He would probably say that the religious experience was one which corresponded to certain spiritual capacities of human nature, the exercise of which is in itself good and desirable apart from their effect upon actual life. And so, too, I think the artist might if he chose take a mystical attitude, and declare that the fullness and completeness of the imaginative life he leads may correspond to</p><p>AN ESSAY IN lESTHETICS</p><p>15</p><p>an existence more real and more important than any that we know of in mortal life. And in saying that, his appeal would find a sympathetic echo In most minds, for most people would, I think, say that the pleasures derived from art were of an altogether different character and more fundamental than merely sensual pleasures, that they did exercise some faculties which are felt to belong to whatever part of us there may be which is not entirely ephemeral and material. It might even be that from this point of view we should rather justify actual life by its relation to the imaginative, justify nature by its likeness to art. I mean this, that since the imaginative life comes in the course of time to represent more or less what mankind feels to be the completest expression of its own nature, the freest use of its innate capacities, the actual life may be explained and justified in its approximation here and there, however partially and inadequately, to that freer and fuller life. Before leaving this question of the justification of art, let me put it in another way. The imaginative life of a people has very different levels at different times, and these levels do not always correspond with the general level of the morality of actual life. Thus in the thirteenth century we read of barbarity and cruelty which would shock even us ; we may I think admit that our moral level, our general humanity is decidedly higher to-day, but the level of our imaginative life is incomparably lower ; we are satisfied there with a grossness, a sheer barbarity and squalor which would have shocked the thirteenth century profoundly. Let us admit the moral gain gladly, but do we not also feel a loss ; do we not feel that the average business man would be in every way a more admirable, more respectable being if his imaginative life were not so squalid and incoherent? And, if we admit any loss then, there is some function in human nature other than a purely ethical one, which is worthy of exercise. Now the imaginative life has its own history both in the race and in the individual. In the individual life one of the first effects of freeing experience from the necessities of appropriate responsive action is to indulge recklessly the emotion of self-aggrandisement. The day-dreams of a child are filled with extravagant romances in which he is always the invincible hero. Music-which of all the arts</p><p>I6</p><p>VISION AND DESIGN</p><p>supplies the strongest stimulus to the imaginative life, and at the same time has the least power of controlling its direction-music, at certain stages of people's lives, has the effect merely of arousing in an almost absurd degree this egoistic elation, and Tolstoy appears to believe that this is its only possible effect. But with the teaching of experience and the growth of character the imaginative life comes to respond to other...</p>